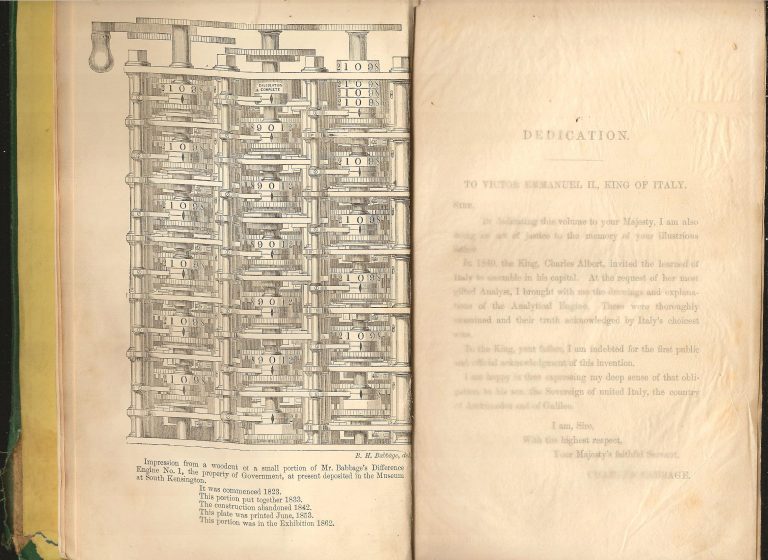

This is my battered first edition of Charles Babbage’s 1864 memoir Passages from the life of a Philosopher. The drawing is of part of his Difference Engine No 1, a precursor to his Analytical Engine, which was a programmable mechanical computer in concept though it was never built.

This is my battered first edition of Charles Babbage’s memoir, Passages from the life of a Philosopher, published in 1864. The drawing shows part of his Difference Engine No 1, a precursor to his Analytical Engine, which was a programmable mechanical computer in concept though it was never built.

Credo

People of my parent’s age would frequently express astonishment at the changes they had witnessed during the first half of the twentieth century with the advent of cars, aircraft, telephones, home appliances, movies, radio, and TV. For the future, most expected more of the same but better, perhaps with added spaceships.

The technology bursting for development at the end of World War Two was so different that it was barely conceivable to anyone but the few brilliant people who brought it into being. Even they could have had only a glimpse of all that it would engender.

Fifty years later, when I had historic objects crossing my desk practically every day as a technology writer in London, people were still struggling with its implications. Twenty-five years on, they still are.

The social effects of what is now called information technology are endlessly discussed because we face them every day. They are so profound that they tend to overshadow another momentous change: both as a phenomenon and as a tool, computers have given us greater understanding of how life works. The insights are fundamental and comprehensive, cutting across common ideas of life, death, the universe and even God. And it seems to me that they have still not completely sunk in.

Doubtless some future generation will come to a working consensus on what it all means and I cannot pretend that my humble opinion could anticipate that. This is the view one of the first generation of people to be confronted with these ideas. It is the story of how I came across them and what I have come to make of them. Speculative, right and wrong, it is a collection of hunches. It is my Credo.

IT seems to me #1

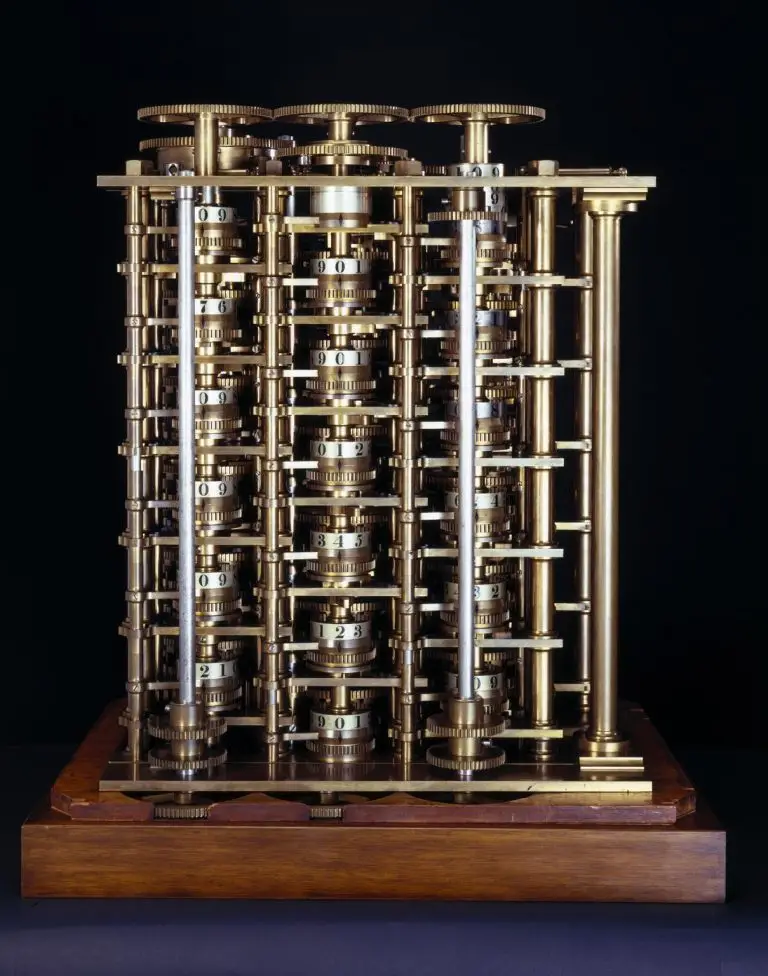

The Difference Engine No 1 (see image top) as crafted by Joseph Clement in 1832 . Science Museum

It seems to me #1

The dawn of the metabrain

My first glimpse of the coming changes came late in 1972, when I was drifting through South America a few weeks after dropping out from my London job. Like most people at the time, I had no notion that computers would very soon become as common and usable as televisions. I had never set eyes on one and had only the haziest idea of what a program was. But I was ploughing through a book called Programming and metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer by John C Lilly, a US scientist and counterculture luminary who described it correctly as barely readable.

Little more than a riff on the idea of the brain as a biocomputer, it had a profound effect on me, and not only because I was reading it under the influence of some very strong Columbian grass — as I relate in my memoir Joker, I came close to flipping out.

People born into the computer age may find it hard to understand just how mysterious the brain was to people with no experience of intelligent machines. It is still mysterious, of course, but we have some idea how it works. In 1972, the word biocomputer alone was enough to transform my view of myself and the world because it shifted my perspective and promised greater understanding to come.

Lilly’s book envisaged the brain as a hierarchy of programs, metaprograms and meta-metaprograms operating at different levels of activity. I had little chance at the time to explore his ideas further – this was two decades before the web browser – but I was exploring the world and I began to see it in their light.

I arrived in Chile a few months before the bloody 1973 military coup that toppled President Allende and the world’s first elected communist government. The country was in political ferment, polarised between a fearful right and a joyful left, with no middle ground for the many people who just wanted to get on with their lives.

While I sympathised with Allende, whose policies seemed to me to be hardly more radical than those of Britain’s post-war Labour government, I felt detached from it all, like a stranger staying with a quarrelsome family. I was fascinated less with what people were saying than with the interplay of opinions and events — all seen with my head full of Lilly’s idea of the biocomputer with its layers of programs and metaprograms.

I wrote in Joker: “Here surely was another layer: brains do not operate in isolation, they interact. Following Lilly’s terminology, I thought of this layer as the metabrain, because just like the human brain it stores and processes information, and makes decisions. I saw it vaguely as the collective intelligence inherent in schools, libraries, the media, communications systems, government and all the other apparatus of human interaction.

“In Santiago, the capital of Chile, I had read a Penguin book called Attitudes, which was simply a collection of papers on that subject. Many of the conclusions were fairly obvious but it was interesting to see them borne out by research. One paper studied reactions to a football match between two American universities during which there had been a certain amount of rough play. Spectators were questioned about controversial incidents in the match, and what they believed they had seen depended very much on which university they came from. Predictably, one side saw a foul where the other saw a touch of artful play.

“People in Chile were both spectators and players in a far more complex game and their views were just as coloured by their personal prisms of attitude which stemmed as much from personal allegiances and circumstances as from a reasoned view of what was best for the country. These attitudes governed whether, for instance, they were willing to believe that Allende was going to set himself up as a Castro-style dictator, or that the crisis had been engineered by the US, or whether they would care if it had. Indeed the US had played a considerable part, but few people at the time were in a position to know for certain.

[Recently declassified documents show that even US intelligence agents were taken by surprise when the coup happened. (Guardian 26.08.23)]

“This was the metabrain in action, wading through a swamp of uncertainty and questions with no good answers. How do you choose between war and subjugation, or war and unwanted change, or instability and oppression? What is the right way to run a country when there is no way of satisfying everybody? The metabrain stumbles on and the only solution is what happens.

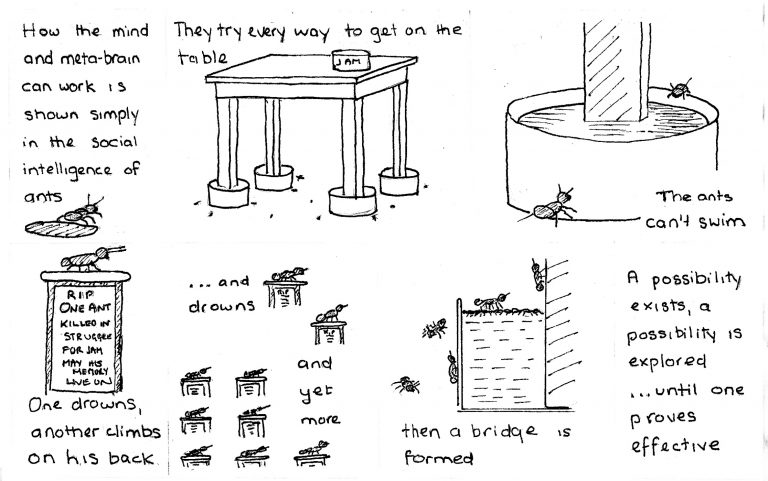

Part of an experimental graphical essay I concocted in the late seventies. The full sequence can be seen in the next section.

“A couple of years later in Goa, India, I became fascinated by an ant colony that kept up a constant attack on our food. We would set the legs of a table in cans of water and stack all our food on top. There seemed no way the ants could reach the food but time and again they got there. Sometimes because someone pushed the table near a wall. Occasionally, because the water evaporated unnoticed. Once, so many ants drowned that their dead bodies formed a bridge. Collectively the ants formed a social intelligence, implementing what I later learned to call an algorithm: if a possibility existed, it was explored. Eventually, with thousands of ants deployed, a possibility was found effective.

“What was effectively an ant metabrain did not seem so different in principle from our own. Individual humans have more nous than an ant, but they are still limited in their perspective and knowledge, negotiating a life too complex even for the metabrain to predict or encompass. All views are incomplete. Nobody knows fully what is going on. Barring catastrophe, the metabrain survives us all, exploring each and every possibility, accumulating knowledge, refining its models of life.”

As I would put it now: only life can compute life.

Clearly the human metabrain was not monolithic; there would be complex interactions at global, local and community-of-interest levels, including some with physical borders. I noted in Joker: “Opinion is geographical. Cross a line on the road and people think completely differently: ogres become saints, heroes become villains, the guns point in the opposite direction. Someone believing in the absolute authority of the Koran on one side of the border might believe with equal conviction in the Bible if they happened to have been born on the other. We are creatures of society as well as our genes. We are creatures of the metabrain.”

It astonishes me to this day that this blindingly obvious fact escapes so many people.

Lilly’s book on the brain was one of the first of its kind and its talk of biocomputer programs draws far too close a comparison with a digital computer. The word metabrain stands up rather better because it avoids that comparison, but the meaning is hard to pin down with precision. Until recently I would have said that the metabrain is to the social mind what the brain is to the mind. But the internet has changed the metabrain, like it changed everything else it touched.

In fact the metabrain has gone through four major changes in the past six thousand years. Prehistoric human culture was largely oral, with little evidence of a tangible metabrain, though ancient cave paintings suggest a wider use of more perishable images and signs. Even ants use signs, in the form of chemical trail markers.

The first step change came with writing, which transformed the world by preserving knowledge, facilitating its dissemination, and allowing distant bright minds to co-operate.

The second came from printing, which accelerated intellectual development by spreading these benefits. It had subtler effects like the consolidation of large states by providing a sense of common identity across a dispersed population.

The third was the advent of the internet, the multiple effects of which we are still trying to assess.

The fourth has only just started and could prove the most momentous. The internet is gaining intelligence. The metabrain is not only mediating the collective mind and storing its knowledge; it is getting a mind of its own. What will become of it in the long term is one of the most fascinating, and perhaps uncomfortable, questions of our times. I have my ideas on that and I’ll come to those anon.

[…] Credo […]